Insatiable Lust

or, The story of how a nice girl from Brooklyn fell hard for books and amassed a collection spanning nine centuries

Lisa Unger Baskin

Bookshelves in my library—the books are double- and, in some instances, triple-shelved. Shown here: the Italian Renaissance, Morata, Colonna, Valeria Miani, Mary Wollstonecraft, Sappho, Elizabeth Elstob, women printers, Pethick-Lawrence Collection, Senault, Pope Joan, Orra White Hitchcock, among others. On the table: figurines and ceramic ware of the Ladies of Llangollen next to a "Votes for Women" bluebird. Photograph by Annie Schlechter, 2014. (view fullsize version)

I suppose there must have been a time when I didn't collect something, but I really don't remember one. The book closet in my bedroom on East Nineteenth Street and Glenwood Road in Brooklyn was a repository for the books, papers, and ephemera that I was gathering (though I did not yet know the word ephemera). Shelved from floor to ceiling, my books were neatly arranged. It was my childhood haven. I was not content borrowing books from the public library—those books had to be returned. I needed to own the books. I was a collector.

While an undergraduate at Cornell I was exposed to special collections. That experience, though brief, opened a door to the historical importance of collecting; I interpreted it in a personal way.

By the mid-sixties my husband and I were collecting, both together and individually. Omnivorously. We collected medals and plaquettes, Mocha ware, rewards of merit, ephemera, and early illustrated books; as well as chiaroscuro woodcuts, color printing, Rudolf Bresdin and Hendrik Goltzius, the d'Agotys, Altdorfer, model books, and ornament prints—all of these things that were not yet particularly sought after by others and not yet expensive. Our pockets were not as deep as our passion for stuff, and we often sold some things to allow us to acquire others. We sold our emblem books, color printing, Goltzius collection, Mocha ware and chiaroscuro woodcuts. There were, however, things that were sacrosanct. My growing collection of Käthe Kollwitz and Paula Modersohn-Becker prints, for example. In the mid-nineteen sixties, we were collecting early illustrated books, among them some printed or illustrated by women. I bought Maria Sibylla Merian's De europische insecten (Amsterdam, 1730) around 1966.

The part that my husband Leonard Baskin played as I formed my collection is without measure. It gave him enormous satisfaction to find treasure for me. His small watercolor cards at Christmas and birthdays that always accompanied gifts of books, manuscripts, or objects would often depict a woman at a printing press or in her bindery—reflecting his understanding of what I was about in collecting the myriad stories of women.

Christmas and birthdays were occasions for gifts to my women's collection. My husband delighted in finding treasure for me. Often the gifts carried a small drawing related to the object. The miniature portrait, E.G., accompanied the gift of a copy of Emma Goldman's My Disillusionment with Russia. Leonard Baskin, E. G., ink and gouache, 1979; and Woman at her hand press, pen ink and gouache, 1996.

In the 1960s, I actively began collecting things relating to women. The core of the collection was, and is, social history. My politics informed my collecting. The anti-war and civil rights movements were part of my growing up in the 1950s. At age thirteen, I was influenced by adults returning from the Freedom Rides and voting rights campaigns in the South. My own civil disobedience was first in response to the Vietnam War. I supported Eugene McCarthy's 1968 presidential campaign. Later, the strains of my activism combined as I organized and co-chaired the Western Massachusetts Rainbow Coalition. I was elected a delegate to the Democratic Convention in 1988 pledged to the Rev. Jesse Jackson. As a young person, I had been radicalized; as an adult, I have continued working to achieve a more just and equitable world.

Women's history and black history are tightly woven together; both are hidden and rarely taught in schools. The women's movement and my compelling interest in these untold stories ultimately directed my passion to help fill in the history of ordinary women—women who worked every day without recognition or acknowledgement. Sidney Kaplan—our close friend, backdoor neighbor, and the editor of the Gehenna Press—is the person who enlightened me and first spoke to me of Phillis Wheatley and the utopian Northampton Association that had attracted Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, David Ruggles, Lydia Maria Child, and Sophia Foord to Northampton, Massachusetts. The relationships between Douglass, Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were evidence of the powerful ties between the anti-slavery and suffrage movements.

During the beginnings of the women's movement in the late sixties, Patricia Holland was in my consciousness-raising group. She was writing her dissertation and editing the letters of Lydia Maria Child. She and Ann Gordon became the editors of the Stanton and Anthony Papers Project, located in New Africa House at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. Women's suffrage and African American history were here joined together. Working with them contributed to my growing knowledge. I organized and curated the first exhibition at the Elizabeth Cady Stanton House at the Women's Rights National Historical Park in Seneca Falls. At UMass I curated an exhibition marking the two hundredth anniversary of the death of Phillis Wheatley.

Left: Sojourner Truth. Narrative of Sojourner Truth, A Northern Slave. . . . Published for the Author, New York, 1853. Truth dictated, published, and sold her narrative to support herself. This copy, with a variant binding, has the imprint "Boston: Published for the Author, 1854." Right: A letter from one of my greatest heroines, Lydia Maria Child, replying to a Mr. Strickland about another hero, the "Noble old man" John Brown. "I shall never again witness such moral heroism as was brought out by the struggle of Freedom with Slavery," she writes.

The historian Michelle Aldrich, an archivist of science, was also in my consciousness-raising group. When we established the Valley Women's Center, she created an archive of papers generated during that new wave of the women's movement. She impressed upon me the necessity of documenting an historical moment through collecting papers. With Lee Edwards and Mel Heath, two others from my group, I co-edited special issues of the Massachusetts Review—Woman: An Issue (Winter/Spring 1972), followed by Woman: The Arts 1 and 2 (1983)—and in the process I was drawn, once again, to the work of early women artists and activists.

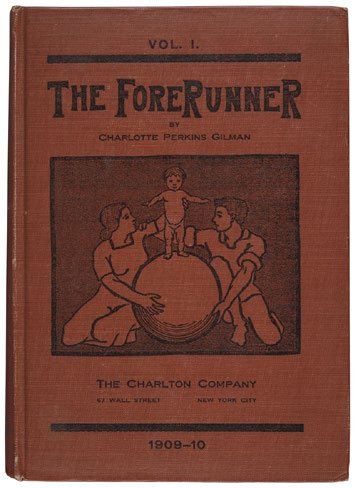

You can't do it alone! The members of the antiquarian book trade have been my stalwart companions. In the later sixties, I was active as a dealer in the antiques and book trades and exhibited at fairs. For some years I kept an open shop during the summer months where I sold books as well as paintings, pottery, and works on paper. I scoured the coast of Maine during our summers on Little Deer Isle. We went “booking” frequently in Maine and Massachusetts. Avis and Rocky Gardner, Betsy and Timothy Trace, Sam Murray, Benny Tighe, Francis O'Brien, and Aimee MacEwen were among the booksellers who provided significant additions to my growing collection. Avis and Rocky were constantly on the road, scouting the country for antiques and paper. I acquired from them the anarchist journal Lucifer, Stanton and Anthony's The Revolution, Emma Goldman's Mother Earth, as well as The Woman's Advocate, the anti-slavery weekly The Standard, Charlotte Perkins Gilman's The Forerunner, and myriad piles of women's suffrage ephemera. To my knowledge, the run of The Revolution in the collection is the most complete extant. Booksellers and antiques dealers were learning about me, beginning to comprehend broadly the delineation of my subject. Responding to my intense focus, they had begun to find things that documented women's history.

Gilman drew the cover image and wrote the entire contents of The Forerunner. Each of the seventy-five individual issues from 1910 to 1916 were acquired in the late sixties from Avis and Rocky Gardiner. The collection also includes this single bound copy of volume 1 (1909–1910) in a publishers binding of Gilman's design.

Somewhere around 1967, I visited a Madison Square Garden Flea Market, going from dealer to dealer asking if they had any "women's things." I went home with a large cardboard box filled with photographs of Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It was my first real "hit." The Adelaide Johnson collection documented her sculpture of Mott, Anthony, and Stanton that now resides in the rotunda of the nation's Capitol. It includes all her preparatory photographs, as well as suffrage calendars, letters, ephemera, and two silhouettes of Lucretia Mott.

As the collection continued to grow, I bought from Tobias Rogers a fine copy of Erasmus Darwin's A Plan for the Conduct of Female Education in Boarding Schools (London, 1797) and John Aylmer's defense of government by women (London, 1559). It was the early books that more and more interested me. Foolishly I did not borrow the money to purchase Alex Rogoyski's collection of early women's books. It's the decision I still regret the most, and it taught me not to hesitate. Find a way. Those opportunities never reoccur—an important lesson. I did ultimately purchase a number of his books when they came to auction in London. But not the entire group of books, alas.

Beware! was printed by the Women's Printing Society with drawings by Mary Lowndes, Dora Meeson Coates, and C. Hedley Charlton. They were all members of the Artists' Suffrage League, which was founded by siblings Clemence and Lawrence Housman. There are two copies in the collection.

In 1973, we moved to England. It was an abundant and significant ten years for me. Living in England during the seventies and early eighties allowed me to build my collection in ways that likely would not have occurred in America. I doubt that the depth of my British suffrage holdings would have been achieved. During this time, I acquired the Pethick-Lawrence Collection, suffrage journals, the New family manuscripts, and objects such as suffrage pins and sashes. I frequently attended the monthly Provincial Booksellers fairs in London. It was there I met the map dealer and suffrage collector Avril Noble, who had formed a serious collection of women's suffrage materials. She was dispersing it slowly. I bought manuscripts and scrapbooks from her, including the account of the suffrage pilgrimage from Birkenhead to London. The scholar-dealer Elizabeth Crawford sold a large Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) tea service to Jeff Towns, from whom I bought it in turn. It is the most complete set known. I first discovered Emily Faithfull at Ian Hodgkins' shop on Connaught Street, acquiring her sister Esther Faithfull Fleet's Bible that had been given to her goddaughter. I began to acquire bindings made by women; my first, by Sarah T. Prideaux (1894), came from Colin and Charlotte Franklin. In Devon, Michael Nott, Paul Gibbs, Gerry Mosdell, and Len Kelly were readily accessible to visit and to buy from.

Printer Emily Faithfull was particularly vested in providing work for women, and to that end she established the Victoria Press for the Employment of Women in 1860. I began acquiring books printed by Faithfull, as well as her letters, after learning of her from Ian Hodgkins and Robin de Beaumont early in my collecting days.

On occasion I attended an auction in London. It was a strictly elderly, white, male world—intimidating and highly competitive. I did, however, manage a few purchases— a Lady Wilde letter and Charlotte Brontë's framed needlework. Jeff Towns, of Dylan's Books, and Hosea Baskin, of Cumberland Rare Books, found and sold to me a copy of Incominciano Le uite de Pontefici et imperadori Romani, the first of two copies I ultimately owned, which was printed by the nuns at a convent press in Ripoli in 1478. My first books by the artist, scholar, and advocate for women's education Anna Maria von Schurman were acquired from Diana Parikian, one of very few women booksellers at the time. My interests expanded to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and my bookseller friends responded. Jeff Towns was integral to my collecting for all our years in England and then some. When Leonard and I returned to western Massachusetts in 1983, Jeff Towns and Eric Korn would arrive from their respective transatlantic journeys on the way to the Boston Book Fair and visit us, their cases filled with treasure.

My collecting focus was not always understood and often not taken seriously. This reflected, I think, the assumption that women didn't have money to buy, resulting in a lack of interest in women customers. It was this disinterest that allowed me to be a stealth buyer. There were, however, a clutch of dealers who were supportive. In the sixties, I discovered that Russell and Martha Freedman had moved nearby to North Adams, Massachusetts, and they were specializing in women's books. With Cheryl Needle I shared politics while acquiring books and manuscripts—including Laura Terracina's Il discorso (Venice, 1638), as well as The Married Woman's Private Medical Companion, the 1847 second edition, the first book to advertise condoms in America. Jake Zeitlin and Lucien Goldschmidt took my collecting seriously. Ken Leach of Brattleboro, Vermont, was magnificently generous to me, and I treasure memories of my visits to his tobacco-suffused book rooms. Leif Laudamus, just over the bridge in Amherst, sold me Torrey's A Portraiture of Domestic Slavery (Philadelphia, 1817), amongst many other books. Carol and Steve Resnick had a ferret's eye similar to my own. Dorothy Johnson and Doris Abramson of the Common Reader Bookshop, Frances Hamill and Margery Barker in Chicago, Barbara Walzer, Kay Gregory, Priscilla Juvelis, Sarah Baldwin, Sharon McBlain, Sheryl Jaeger, Evie Eysenberg, Valerie Jackson-Harris, Paulette Rose, Mary Cooper Gilliam, and PEKL were an impressive group of women booksellers from whom I added to my collection. Margolis and Moss, Bernard Rosenthal, David Block, Fred Schreiber, Jeff Mancevice, Frank McQuaid, Tom Boss, Bolerium, Frannie Ness and Gary Oleson, and David Miles are among the booksellers who have been constant in their willingness to share their knowledge and books. Peter Howard sold me Rideout novels and Abigail Scott Duniway, as well as eighteenth-century pamphlets printed by Anne Baldwin. One day, during a California Book Fair, Peter insisted on driving me to meet David Sachs in Oakland. I am grateful for Peter's friendship, and for transporting me to David's book-packed rooms all those years ago. Leona Rostenberg and Madeline Stern were scholar-booksellers, feminists, and astute businesswomen. They taught me as they sold me the books of Marguerite de Navarre, Vittoria Colonna, Margherita Costa Romana, and Juan Vives. They introduced me to Helen Maria Williams, the revolutionary writer. Nico Israel took me to the Maria Sibylla Merian exhibit in Haarlem; though alas, I could never afford to buy a copy of Merian's Surinam from him. From Jonathan Reilly at Maggs I acquired Agustín's Dialoghi (Rome, 1592) with its illustrations by Geronima Parasole. James Arsenault and Hosea Baskin were responsible for my acquisition of Phoebe Anna Traquair's manuscript In Memoriam (Edinburgh, 1892), on a suggestion provided by Phillip Pirages. And the list could go on—Deborah Coltham, Veronica Watts, Susanne Schulz-Falster, and many more.

Artist and scientist Maria Sibylla Merian is surrounded by metamorphosing insects, books, and engravings—all redolent of her life’s work. This is the frontispiece of her Erucarum ortus of 1717.

Though I had always proclaimed specific cut-off dates for my collection—from 1478 to Emma Goldman and the Spanish Civil War—I was never rigid in keeping to boundaries. I altered them to suit my desires when something tantalizing appeared. Thus the earliest item in the collection is a grant of land from 1240, and the collection reaches into the mid-to late-twentieth century. The scope of my collection continued to expand, embracing women booksellers, photographers, the law, publishers' bindings, science and medicine, labor and anarchism, and trade cards that show how women could and did earn a living. It is not a literary collection, with a few exceptions such as the Brontës and a good holding of Sarah Orne Jewett, who is included for her stories as well as binding designs by the artist Sarah Wyman Whitman. I also acquired objects, including pottery, a ceramic artist's paint box, and the great WSPU banner from 1910 that hung in my library proclaiming JUSTICE, the underlying theme sewing the disparate parts of my collection together.

The 4th Grade Class, Roach Street School, Atlanta, Georgia, in 1896 with their unidentified teacher beside them.

It was not until twenty or thirty years into this work that I began to understand the significance of the collection that I had been so assiduously gathering. Sometime around 1986, Charlotte and Colin Franklin came to visit us in Leeds and saw my women's collection together for the first time. In our low-ceilinged, seventeenth-century house in Devon, the collection had been parceled into various small rooms. Now, seeing it all together in my Massachusetts library, Colin said, "The desk belongs here." He was referring to Virginia Woolf's early writing desk, which lived in his Elizabethan book barn in Culham, Oxfordshire, and which was not for sale. We came to an understanding, and Woolf's desk joined the collection. It is now safe and available for all to see at Duke's Rubenstein Library.

Left: Lilly Geiger's Victorian trade card reveals that at some point the traditional role of women tending to the dead became a means to earn a living. Right: Ephemeral eighteenth-century women's trade cards help document the history of working women. Eleanor Ogle. Fruiterer at the Lemon Tree in Covent Garden. London, ca. 1760.

The magic of seeing and holding an original object—a notebook recording sewn piecework with the prices paid to the dressmaker, a needlework wrought by Charlotte Brontë, Phillis Wheatley's signature on the reverse of her title page—conjures the spirits and lives of working women. The heart of my collection, the reason for its existence, was always about imparting knowledge, about recording and remembering, about saving the stories and affirming the contributions that women made throughout the millennia. The limitations of language and the geographic focus solely on Western Europe and the Americas are shortcomings, but the collection continues to grow. It is deeply satisfying that my collection sits so well in its new home at the Rubenstein Library. The overlaps and intersection with Duke's comprehensive History of Medicine Collection and the John Hope Franklin Center for African and African American History and Culture are significant to me. To continue collecting collaboratively with the Sallie Bingham Center for Women's History and Culture is a rare opportunity; this joining together is unique.

The Lisa Unger Baskin Collection is a teaching collection. It was always my intention that the collection have a useful life in its next iteration, to be available to students, researchers, and ordinary people who might find inspiration in women's work and accomplishments, achieved even as they were burdened and oppressed. In its new context the collection will continue to grow, to educate, and to spark the kind of unexpected connections that made it such a labor of love.